![]()

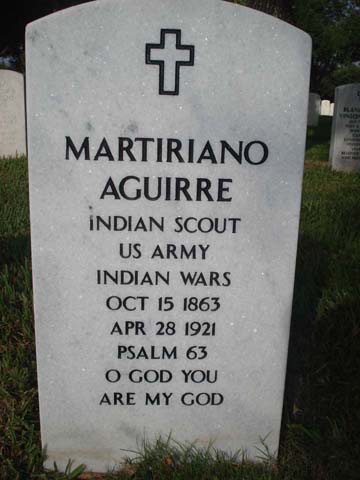

Martiriano Aguirre

Indian Scout US Army

Indian Wars

FORT SAM HOUSTON, Texas (Army News Service,

Dec. 6, 2006) - With the sound of Taps and the sweet smell of sage still

lingering in the air, the military and Native American communities laid an

American Soldier to rest Friday who served, and died, more than a century ago.

Martiriano Aguirre, a Yaqui Indian who served in the Indian Wars, was reburied

with full military and Native American honors at the Fort Sam Houston National

Cemetery in the presence of three generations of descendants, all raised on

tales of the Army private's courage.

As the flag-draped coffin arrived, Michael Aguirre tearfully watched as a

seven-year journey to bring honor to his great-grandfather came to an end.

"Martiriano was very brave and served with honor, but never received military

recognition for his service," said Michael, who spearheaded the efforts to

re-inter his great-grandfather at the Fort Sam Houston cemetery. "This was a

long-time coming."

After a 3-volley rifle salute, two Soldiers removed the U.S. flag from the

coffin and meticulously folded it for presentation to Armando Aguirre,

Martiriano's grandson and one of many family members in attendance.

As military honors concluded with the sounding of Taps, a representative from

the Native American community stepped forward to utter an Indian prayer in an

ancient language. He waved a burning bundle of sage in each direction, then

turned to drift the sweet-smelling smoke around the coffin.

"I came to give a blessing to a brother, a last prayer to release him to our

creator," said Richard Naateh Luna, a Korean War veteran from the White Mountain

Apache tribe. Luna presented Armando with a feather in honor of his grandfather.

To thank his great-grandfather for his legacy, Michael raised a replica of the

sword from the movie "Braveheart" in tribute. "I raise this sword to honor you

great-grandfather."

Martiriano's descendants carried the coffin to the gravesite.

Armando said he was touched beyond words by the re-interment ceremony. "It's a

beautiful thing. He didn't speak English, but he was a good tracker. My

grandfather served; he deserved this honor," said the World War II veteran.

"Because of men like him, Texas is what it is today," Michael said.

Like most early Americans, Martiriano pulled himself up by his bootstraps. He

came from the poverty-stricken Yaqui Indian tribe in Mexico, a looked-down-upon

group of Indians persecuted by both the Mexicans and other Indian tribes. His

people were murdered, abused and forced from their home in Sonora into the

YucatAfA!n peninsula, where they were sold as slaves and worked on plantations.

"They were considered the lowest form of society," Michael said.

Seeking a better life, Martiriano jumped at the chance to join the U.S. Army,

which was in West Texas recruiting Indians for scouts. In return, the men would

receive pay and rations.

The 15-year-old joined the Army in 1878. His enlistment papers describe him as

22 years old, 5 feet, 5 inches with a copper complexion.

The private served for four years in the Indian Wars, mostly under Lt. John

Bullis. Under Bullis' command, the Seminole-Negro Indian Scouts, mostly

descendants of escaped slaves, engaged in 12 battles on both sides of the border

without losing a single scout in combat, according to the Fort Davis National

Historic Site. The scouts became known for their tracking and marksmanship

skills, as well as bravery in battles between the Army and Indian tribes.

"The Army could send the scouts out with half the rations of regular Soldiers

and they could survive," said Michael. Michael recalled a story his father

passed down to him about Martiriano. "The scouts were on a mission in New Mexico

and the Soldiers ran out of water. Martiriano stood on his saddle and started to

sniff for water. He led them to a place and started to dig. There was water

there."

Michael said a well in that spot was named after his great-grandfather because

of that feat.

After his service, Martiriano moved to San Antonio and worked as a barber until

he died in 1921. His family placed a wooden cross on his grave at the San

Fernando Cemetery in San Antonio, never realizing his four years of service had

earned him a military burial.

"My family was poor and my grandparents sacrificed to bury him there," Michael

said.

Michael's father petitioned the government for a military headstone, which was

placed at his grave in 1969. However, a military cemetery is where Martiriano

truly belonged, Michael said.

"I felt he deserved recognition for his service," he said. Michael went on a

crusade, and spent seven years unsuccessfully seeking funding assistance for a

military funeral from politicians and corporations throughout the nation. "I got

shot down by everyone," he said. "I was close to giving up."

But then a friend of his suggested he try the chief's group at Lackland Air

Force Base, where he worked as an electrician for the 37th Civil Engineer

Squadron. With one call, he found the help he was seeking.

"The enlisted men and women of Lackland Air Force Base didn't hesitate to

support Michael," said Chief Master Sgt. Dwayne Hopkins, 37th Training Wing

command chief, who led a formation of Airmen from Lackland Air Force Base during

the funeral. "Martiriano was enlisted and he is an American. That is why we made

this happen. We take care of our own."

Michael said he is grateful to the troops at Lackland Air Force Base, the Fort

Sam Houston National Cemetery and the family and friends who wouldn't let him

end his quest.

"It feels good to have this journey come to an end," Michael said. "I didn't

know the man but I am so glad to have honor brought to him.

"This ceremony isn't just to honor him, but all of the scouts who served with

such bravery and honor."

(Elaine Wilson writes for the Fort Sam Houston Public Information Office.)

![]()

©2001-Present

Linda

Simpson

![]()

08/02/2015